Nigeria:

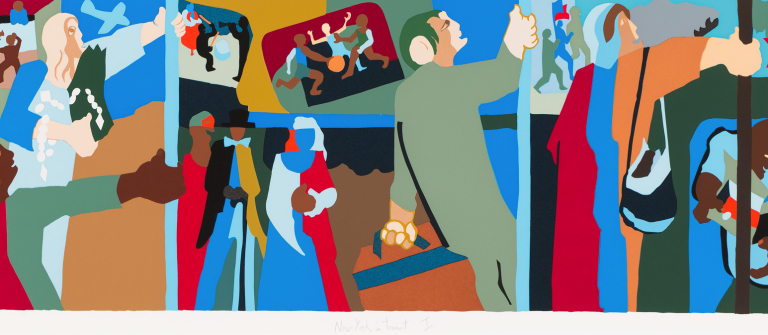

"Carpenters" lithograph by Jacob Lawrence in the Bruce Museum exhibition"ReTooled: Highlights from the Hechinger Collection." photo: Joel Breger

Born in Atlantic City, New Jersey, Lawrence grew up in Harlem during the Depression. Harlem was an active cultural center then, and Lawrence became interested in the arts while still a teenager. He received early training at art workshops sponsored by the federal government's Works Progress Administration (WPA) in Harlem and then studied at the American Artists School in New York. From 1938 to 1939, Lawrence worked in the Federal Arts Project and produced some of his earliest major works. His first important solo exhibition in 1944, at New York's Museum of Modern Art, secured his place as an important commentator on the American scene, particularly African American experiences. Lawrence died on 9 June 2000.

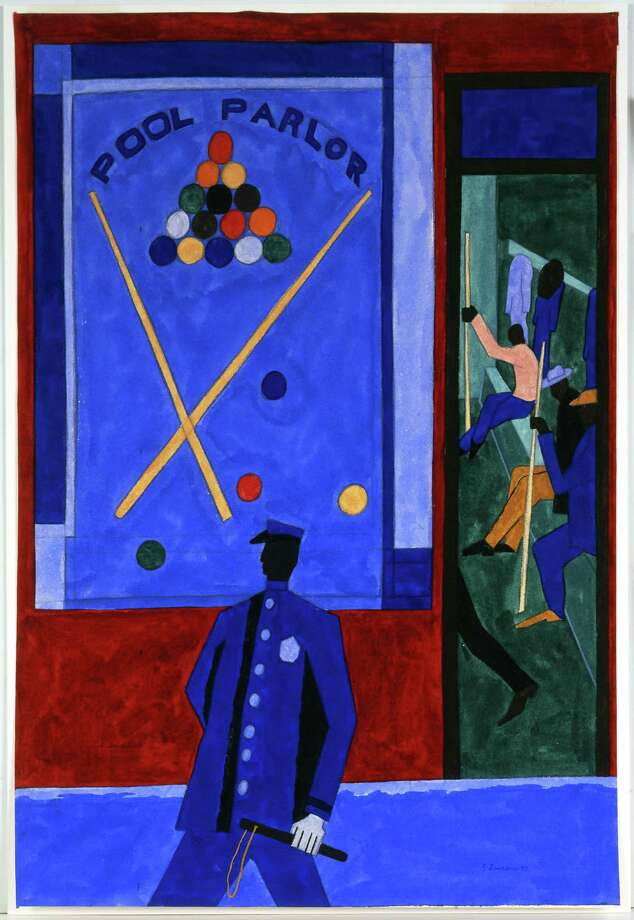

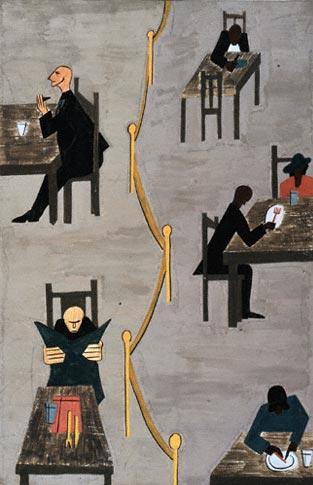

Lawrence's subject matter and painting style remained relatively consistent through his career. His subjects range from street scenes to the lives of important African Americans to powerful narrative series--chronicles of the afflictions endured by African Americans. He portrays these diverse subjects in a quasi-representational style that combines vivid, often discordant tempera colors with a flattened, fragmented treatment of form and space. The artist's intent is to convey his feelings about the subjects portrayed. As Lawrence said, "My pictures express my life and experience. I paint the things I know about and the things I have experienced."

Lawrence referred to his work as “dynamic cubism,” with its bold colors and shapes. He was strongly impacted by artist and childhood mentor Charles Alston, artist Josef Albers of the Bauhaus and the artists of the Mexican muralist movement. His narrative paintings often reflect his personal experience or depict key moments in African American history, including the accomplishments of people such as Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman and the achievements of the American civil rights movement.

Lawrence was the first African American artist to be represented by a major New York commercial gallery and the first visual artist to receive the Spingarn Medal, the NAACP’s highest honor.

Thought missing for decades, the panel will be reunited this week with the artist's Struggle series, now on view in an exhibition at The Met that closes November 1, 2020.

The work will also join the exhibition tour, organized by the Peabody Essex Museum, and be on view at subsequent venues through fall 2021.

The Met has announced the discovery of a painting by esteemed American artist Jacob Lawrence that has been missing for decades. The panel is one of 30 that comprise Lawrence's powerful epic, Struggle: From the History of the American People (1954–56), and it will be reunited immediately with the series, now on view at The Met through November 1 in Jacob Lawrence: The American Struggle. Titled by the artist There are combustibles in every State, which a spark might set fire to. —Washington, 26 December 1786, the work depicts Shays' Rebellion, the consequential uprising of struggling farmers in western Massachusetts led by Revolutionary War veteran Daniel Shays; it protested the state's heavy taxation and spurred the writing of the U.S. Constitution and efforts to strengthen federal power. The panel is number 16 in the Struggle series.

The painting has not been seen publicly since 1960, when the current owners purchased it at a local charity art auction. A recent visitor to The Met's exhibition, who knew of the existence of an artwork by Lawrence that had been in a neighbor's collection for years, suspected that the painting might belong to the Struggle series and encouraged the owners to contact the Museum.

The work will be specially featured at The Met and will also join the touring exhibition, organized by the Peabody Essex Museum (PEM), for presentations in Birmingham, Alabama; Seattle, Washington; and Washington, D.C., through next fall.

Max Hollein, Director of The Met, said, "It is rare to make a discovery of this significance in modern art, and it is thrilling that a local visitor is responsible. We are also very excited for our colleagues at the Peabody Essex Museum (PEM), the organizers of the exhibition that inspired this historic find. And most importantly, we are looking forward to having visitors enjoy this new addition—in these final two weeks at The Met and at the upcoming venues of the show."

Before this discovery, five of the 30 panels painted by Lawrence for the Struggle series were unlocated, and two of those were recorded only by their titles. The "Shays' Rebellion" panel is one of those. Its existence was known through a brochure that accompanied the first showing of the Struggle series in New York in December 1956 at the Alan Gallery. In May 1958, the panels were exhibited again at the gallery, and had not been seen together as a group until PEM's 2020 organization of Jacob Lawrence: The American Struggle.

"It was our fervent hope that the missing panels would somehow surface during the run of American Strugglein New York, the city where Lawrence spent most of his life and where the series was last seen publicly," said Randall Griffey, Curator in the Department of Modern and Contemporary Art, and Sylvia Yount, Lawrence A. Fleischman Curator in Charge of the American Wing, who co-organized The Met's presentation of the exhibition. "Lawrence's dynamic treatment of the 1786–87 Shays' Rebellion reinforces the overall theme of the series—that democratic change is possible only through the actions of engaged citizens, an argument as timely today as it was when the artist produced his radical paintings in the mid-1950s."

"Since reuniting the Struggle series, the absence of panel 16 has been felt acutely. Represented in our galleries as an empty frame, it was a mystery that we were all eager to solve," said Brian Kennedy, PEM's Rose-Marie and Eijk van Otterloo Director and CEO. "We are thrilled to learn of its discovery—one that came about thanks to close looking and careful observation by a museum visitor—and appreciate the generosity of panel 16's owner to have it join and help relaunch the national tour of Jacob Lawrence: The American Struggle."

Jacob Lawrence: The American Struggle features the series of paintings Struggle . . . From the History of the American People (1954–56) by the iconic American modernist. The exhibition reunites the multi-paneled work for the first time in more than half a century.

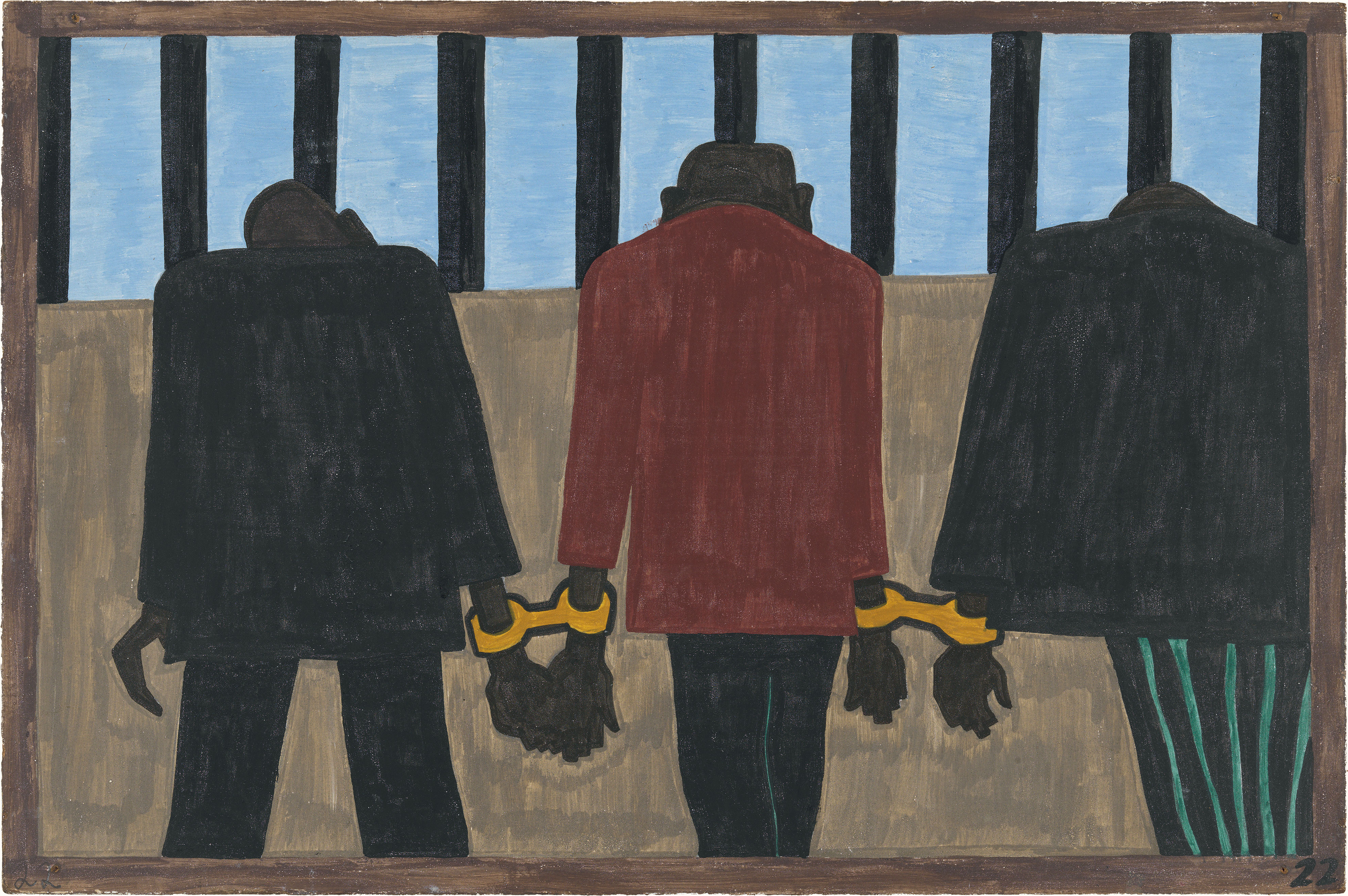

One of the greatest narrative artists of the twentieth century, Jacob Lawrence (1917–2000) painted his Struggle series to show how women and people of color helped shape the founding of our nation. Originally conceived as a series of sixty paintings, spanning subjects from the American Revolution to World War I, Struggle was intended to depict, in the artist’s words, “the struggles of a people to create a nation and their attempt to build a democracy.” Lawrence planned to publish his ambitious project in book form. In the end, he completed thirty panels representing historical moments from 1775 through 1817—from Patrick Henry to Westward Expansion. The 12- x 16-inch panels that comprise Struggle feature the words and actions of not only early American politicians but also of enslaved people, women, and Native Americans to address the diverse but mutually linked fortunes of all American constituencies engaged in the struggle. Taken as a whole, this remarkable series of paintings interprets and expresses the democratic debates that defined early America and still resonate today.

:focal(908x668:909x669)/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/af/f6/aff670aa-4763-4ace-aa1f-bd6568dd3b83/presspanel81800_002a.jpg)

Between 1949 and 1954, Jacob Lawrence made countless trips from his home in Brooklyn to the 135th Street Branch of the New York Public Library, where he scoured history books, letters, military reports and other documents for hidden stories that had shaped American history. By this point in time, Lawrence was “the most celebrated African American painter in America,” having risen to fame in the 1940s with multiple acclaimed series depicting black historical figures, the Great Migration and everyday life in Harlem. In May 1954, just as the Supreme Court ruled to desegregate public schools, the artist finally finished his research. He was ready to paint.

\According to Nancy Kenney of the Art Newspaper, Lawrence’s series was purchased privately in 1959 and later sold off “piecemeal.” The whereabouts of five of the paintings are unknown, and several others were deemed too delicate to travel; they are represented by reproductions.

Though the collection is incomplete, the new show offers a sweeping look at Lawrence’s remarkably human exploration of the country’s formative years.

“These are history paintings like you have never seen before,” says Lydia Gordon, PEM’s associate curator for exhibitions and research, in a museum blog post.

The series blends the boundaries between figuration and abstraction, and as its name suggests, struggle is a central theme. Lawrence’s scenes are angular and tension-filled, with thin lines of blood often dripping from characters. His interpretation of George Washington crossing the Delaware does not show the general standing majestically at the helm of a boat, as seen in Emanuel Leutze’s famed painting of the same subject. Instead, Lawrence’s preoccupation is with the nameless soldiers who fought and died for American independence. Here, these figures are shown huddled and cloaked, their bayonets jutting over the river like spikes.

Another one of Lawrence’s central concerns was the role of African Americans in the nation’s founding.

“[T]he part the Negro has played in all these events has been greatly overlooked,” he once said, as quoted by Sebastian Smee of the Washington Post. “I intend to bring it out.”

One panel depicts Patrick Henry’s famed 1775 call to arms against the British. The artwork is captioned with a line from Henry’s speech: “Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery?”

Still, the Patriots’ fight against bondage failed to encompass the country’s actual enslaved individuals. Yet another panel in the series shows African Americans in the throes of revolt.

“We have no property! We have no wives! No children! We have no city! No country!” reads the caption, which quotes a letter by Felix Holbrook, a slave who petitioned for emancipation in 1773.

Struggle also highlights the enslaved men, Creole people, and immigrants who fought with Governor Andrew Jackson in the 1815 Battle of New Orleans; the anonymous laborers who toiled to build the Erie Canal across New York state; and the contributions of Margaret Cochran Corbin, who followed her husband into the Revolutionary War and, when he was killed, took over firing his cannon. She became the first woman to receive a military pension—one that was “half the size of the men’s,” according to the museum. In Lawrence’s panel, Corbin is turned away from the viewer, a pistol tucked into the waistband of her dress.

The year he started painting Struggle, Lawrence explained that his objective for the series was to “depict the struggles of a people to create a nation and their attempt to build a democracy.” He painted these works during the modern Civil Rights era, knowing the battle was still not finished. Today, says Gordon, Struggle continues to resonate.

“[Lawrence’s] art,” she adds, “has the power to encourage difficult conversations that we need to be having: What is the cost of democracy for all?”

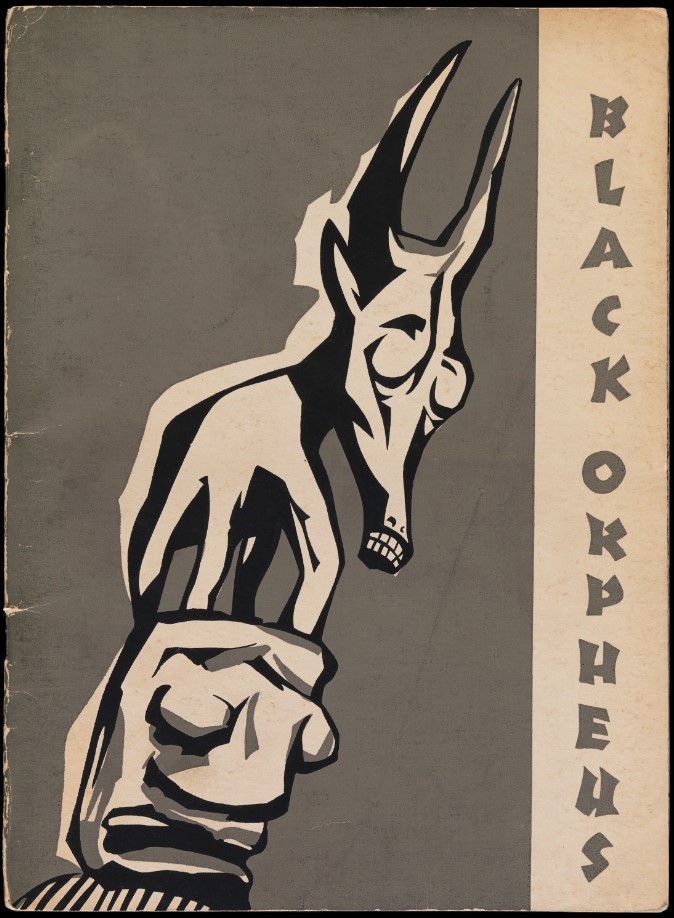

Black Orpheus: Jacob Lawrence and the Mbari Club

Chrysler Museum

October 7, 2022, to January 8, 2023

New Orleans Museum of Art

February 10 to May 7, 2023

Toledo Museum of Art

June 3 to September 3, 2023

The exhibition features more than 125 objects, including paintings, sculptures, reliefs and works on paper. Lawrence’s Nigeria series (1964-65) anchors the exhibition and appears alongside works by several Mbari Artists and Writers Club members, including Duro Ladipo, Twins Seven-Seven, Muraina Oyelami, Asiru Olatunde, Jacob Afolabi and Adebisi Akanji. The show also includes letters Lawrence wrote to his friends in the United States about his experiences in Nigeria and copies of Black Orpheus (1957-67), the Nigeria-based literary journal that showcases the works of modernist African and African Diasporic writers and visual artists.

“The Toledo Museum of Art holds several works by Jacob Lawrence in the permanent collection. Black Orpheus: Jacob Lawrence and the Mbari Club presents an important opportunity to broaden our understanding of Lawrence’s life as well as the history of modernism as a transcontinental phenomenon. This exhibition aligns strongly with the Toledo Museum of Art’s belief that a more inclusive narrative of art history is a truer one, and we could not be more excited to host this important and visually stunning show,” said Adam Levine, the Toledo Museum of Art’s Edward Drummond and Florence Scott Libbey director.

Kimberli Gant, Ph.D., the exhibition’s co-curator, embarked on the research nearly six years ago to bring together artworks from institutions and private collections around the world along with out-of-print copies of Black Orpheus magazine. Together, the objects transport visitors to Nigeria during a time when several countries in Africa and around the world were establishing their independence from European colonialism. Black Orpheus displays how artists grappled with representing their respective national and cultural identities while depicting visually striking works during the beginning of the postcolonial period throughout the African continent and other parts of the world. The resulting objects were meant to resonate with local communities while connecting to broader Eurocentric notions of modernity.

“As the civil rights movement peaked in the United States, Jacob Lawrence traveled to Lagos. Last year marked the 60th anniversary of his first exhibition and visit to Nigeria and the 65th anniversary of Black Orpheus,” said Gant. “This show is the first museum exhibition of Lawrence’s Nigeria series and introduces new scholarship about a little-known period in his life that included a nine-month stay in Nigeria in 1964. Through the works on view, visitors will gain insight into Lawrence’s conversations with Nigerian, Ethiopian, Sudanese and Ghanian artists and discover how those interactions influenced him long after he returned to the United States. Lawrence’s global impact is also evident in the works on view by other international artists.”

The exhibition is organized into five sections that offer insight into Lawrence’s experiences and emphasize the global diversity of the artists affiliated with Black Orpheus and the Mbari Artists and Writers Club. Nigeria, the first section of the exhibition, introduces viewers to Lawrence’s representation of the country through depictions of its splendid markets, complex communities and permeable spiritual practices. Artists of Osogbo follows with works of several little-known Nigerian artists who learned a range of artistic traditions—printmaking, batik textiles and painting—from older generations of Western and non-Western artists. Their images inspired younger generations. Zaria Art Society showcases a small group of Nigerian artists who met at the National College of Art & Technology and developed a philosophy called “natural synthesis,” where the artists incorporated local aesthetics and cultural traditions with western-style art techniques to create a new modern art form. Across the African Continent features artists from other countries outside of Nigeria who also trained in European art styles yet featured iconography and stories from their own cultures as modes of new artistic expression. The exhibition concludes with Beyond the African Continent, featuring artists from around the world whose dynamic creations mirrored those of their counterparts in Africa.

“This exhibition highlights artists based outside the accepted art centers of the United States and Europe and reveals the nuances of global modernist art practices during the mid-20th century,” said Gant. “Some used their artistic practice to reflect Nigeria’s and Africa’s post-colonial era while others communicated the sociopolitical issues they were facing in their respective countries. Lawrence’s Nigeria series represents an ongoing legacy of African American artists venturing to the African continent for knowledge and inspiration.”

Black Orpheus: Jacob Lawrence and the Mbari Club is co-organized by the Chrysler Museum of Art and the New Orleans Museum of Art. It is curated by Kimberli Gant, Ph.D., the Brooklyn Museum’s curator of modern and contemporary art and the Chrysler Museum of Art’s former McKinnon curator of modern and contemporary art, and Ndubuisi Ezeluomba, Ph.D., the Virginia Museum of Fine Art’s curator of African art and the New Orleans Museum of Art’s former Françoise Billion Richardson curator of African art.

A full-color catalogue published by Yale University Press will accompany the exhibition and include essays by the exhibition curators and preeminent scholars including Leslie King Hammond and Peter Probst as well as a new generation of scholars bringing forward new scholarship including Suheyla Takesh, Katrina Greven and Iheanyi Onwuegbucha.

Jacob Lawrence (American, 1917–2000), Market Scene, 1966. Gouache on paper. Chrysler Museum of Art, Museum purchase 2018.22. © 2022 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Cover of Black Orpheus Journal #5, May 1959 Collection of Philip Peek, Sanbornton

Photo: Sesthasak Boonchai

Exhibition Catalogue

This multi-authored volume, featuring contributions by contemporary art historians, cultural historians, and artists, examines Lawrence's epic American history series in diverse contexts that resonate profoundly today.

- Jacob Lawrence, “Firewood #55” (1942): Lawrence created this gouache, ink and watercolor on paper during his first trip to the rural South. In the work, an African-American woman sorts firewood against a sparse landscape, which emphasizes the hardships of farm life in the Depression era.

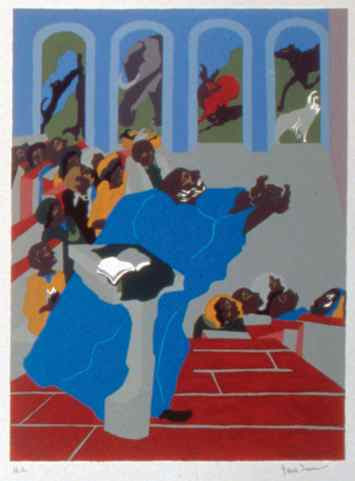

40. Jacob Lawrence (1917-2000)

Toussaint L'Ouverture series, No. 17: The Capture, 1987

Silkscreen

28 x 18 1/2 inches

The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.

Gift of Amistad Research Center, 1987

The installation demonstrates Lawrence’s gift for observing life and telling a story, whether he was capturing the everyday details of Harlem or reconstructing critical moments in African American history. His bold, abstract yet figurative style—a hybrid European Cubism and early 20th-century Social Realism—is also apparent in the 39 prints, which include a complete set of his first print portfolio,

and an artist’s proof edition of Eight Studies for “The Book of Genesis” (1989–1990).

More on the Legend of John Brown graphic series:

Consisting of twenty-two silk-screen prints, the portfolio is based on Lawrence’s same-size gouache paintings from 1941 (owned by the Detroit Institute of Arts) that explore the life of the controversial abolitionist. In 1977, when the paintings had become too fragile for public display and access, the Detroit museum commissioned Lawrence to reproduce them as limited-edition screen-prints. Each painting was originally displayed with the artist’s accompanying text, which builds on the powerful visual narrative. Lawrence’s John Brown series was among the historical epics he produced in the 1930s and 1940s focusing on heroic 19th-century figures like Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass as well as the Great Migration of the early 20th-century.

As Lawrence explained: “The inspiration to paint the Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman and John Brown series was motivated by historical events as told to us by the adults of our community . . . the black community. The relating of these events, for many of us, was not only very informative but also most exciting to us, the men and women of these stories were strong, daring and heroic; and therefore we could and did relate to these by means of poetry, song and paint.”

From a review:

Notable pieces include “The Ordeal of Alice,” a wrenching portrait of a young black girl clutching her school books, shot by arrows like Saint Sebastian, a representation of the racial violence surrounding attempts to integrate public schools.

A powerful visual epic, The Migration Series (1940–41) documents the historic movement of millions of African Americans from the rural South to the urban North more than a century ago. Reuniting 30 panels owned by the Phillips with 30 panels on loan from the Museum of Modern Art, Lawrence’s complete series will be on display beginning October 8, 2016, and will run until January 8, 2017.

Jacob Lawrence, The Migration Series, Panel no. 1: During World War I there was a great migration north by southern African Americans, 1940–41. Casein tempera on hardboard, 12 x 18 in. The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC, Acquired 1942 © The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

“In panel 60 of The Migration Series, Lawrence leaves us with the message, ‘And the migrants kept coming,’” said curator Elsa Smithgall. “During a time when record numbers of migrants are uprooting themselves in search of a better life, Lawrence’s timeless tale and its universal themes of struggle and freedom continue to strike a chord not only in our American experience but also in the international experience of migration around the world.”

Jacob Lawrence, The Migration Series, Panel no. 24: Their children were forced to work in the fields. They could not go to school., 1940–41. Casein tempera on hardboard, 12 x 18 in. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Mrs. David M. Levy © The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Jacob Lawrence, The Migration Series, Panel no. 37: Many migrants found work in the steel industry., 1940–41. Casein tempera on hardboard, 12 x 18 in. The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC, Acquired 1942 © The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Jacob Lawrence, The Migration Series, Panel no. 45: The migrants arrived in Pittsburgh, one of the great industrial centers of the North., 1940–41. Casein tempera on hardboard, 12 x 18 in. The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC, Acquired 1942 © The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Jacob Lawrence, The Migration Series, Panel no. 49: They found discrimination in the North. It was a different kind., 1940–41. Casein tempera on hardboard, 12 x 18 in. The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC, Acquired 1942 © The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Jacob Lawrence, The Migration Series, Panel no. 50: Race riots were numerous. White workers were hostile toward the migrant who had been hired to break strikes., 1940–41. Casein tempera on hardboard, 12 x 18 in. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Mrs. David M. Levy © The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Jacob Lawrence, The Migration Series, Panel no. 55: The migrants, having moved suddenly into a crowded and unhealthy environment, soon contracted tuberculosis. The death rate rose., 1940–41. Casein tempera on hardboard, 12 x 18 in. The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC, Acquired 1942 © The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Jacob Lawrence, The Migration Series, Panel no. 57: The female workers were the last to arrive north., 1940–41. Casein tempera on hardboard, 12 x 18 in. The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC, Acquired 1942 © The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Jacob Lawrence, The Migration Series, Panel no. 59: In the North they had the freedom to vote., 1940–41. Casein tempera on hardboard, 12 x 18 in. The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC, Acquired 1942 © The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Jacob Lawrence, “New York in Transit I,” 1998, silkscreen, edition of 50 with 5 AP, © 2015 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Featuring more than 90 works produced between 1963 and 2000, the exhibition focuses on his graphic work and explores three major themes of his printmaking oeuvre. Lawrence’s recording and recollection of African-American and larger African diasporic histories are featured, as well as his vivid observations of dynamic city life in Harlem, New York City. Works in the exhibition include significant complete print portfolios, such as the “Toussaint L’Ouverture” series, as well as “The Legend of John Brown” series, amongst others.

A prominent 20th-century artist, Lawrence is renowned for his depiction of African-American life as well as epic narratives of African-American history.

Presented in the Ruth C. Horton Gallery, Sherwood Payne Quillen ’71 Reception Gallery, and Miles C. Horton Jr. Gallery, “History, Labor, Life: The Prints of Jacob Lawrence” features more than 90 works produced by Lawrence from 1963 to 2000.

Lawrence started exploring printmaking as an already well-established artist. Printmaking suited his bold formal and narrative style exceptionally well. The connections between his painting and printmaking were intertwined, with the artist revisiting and remaking earlier paintings as prints. The inherent multiplicity of this medium provided an opportunity for him to reach broader audiences.

Lawrence was primarily concerned with portraying African-American experiences and histories. His acute observations of community life, work, struggle and emancipation during his lifetime were rendered alongside vividly imagined chronicles of the past. The past and present in his practice are intrinsically linked, providing insight into the social, economic, and political realities that continue to impact and shape contemporary society today.

Lawrence spent his formative years in New York City, where his work as an artist was shaped by the intellectual strength and vitality of the Harlem Renaissance, not only in terms of his engagement with such artists as Charles Alston and Augusta Savage, but by the ongoing discourse at the time about writing and giving identity to African-American history.

Lawrence spent months in the 135th Street branch of the New York Public Library, which is now the Schomberg Center for Research in Black Culture, studying historical documents, books, photographs, and journals before creating a series of narrative works that would bring him national recognition. He was only 25 when he became the first African-American artist represented in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York with his “Migration Series” (1941), now considered to be a landmark in the history of American modern art.

During his career, Lawrence received the National Medal of Arts, which is the highest award given to artists and arts patrons by the United States government, as well as 18 honorary doctorates from institutions, including Harvard University, Yale University, New York University, and Howard University. He was a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters and served as a commissioner for the National Council on the Arts.

Today, Lawrence’s work is represented in almost 200 museum collections, including the Art Institute of Chicago; the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.; the Brooklyn Museum of Art; and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

“History, Labor, Life: The Prints of Jacob Lawrence”

Jacob Lawrence (1917–2000) was mentored by Charles Alston and heavily influenced by the writers and artists of the Harlem Renaissance. After receiving a scholarship to the American Artists School in 1937, he soon distinguished himself as an exceptional voice in American painting. From 1941 until 1953, Lawrence exhibited regularly at Edith Halpert’s Downtown Gallery, New York, and throughout the 1950s and early 1960s, he was a regular participant in annual exhibitions at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Today, Lawrence’s work is represented in almost 200 museum collections, including the Art Institute of Chicago, Illinois; the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.; the Brooklyn Museum of Art; the Studio Museum in Harlem; and The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Lawrence was the first African-American artist to be represented by a major commercial gallery. During his prolific career, Lawrence was presented with numerous awards and accolades. He earned the National Medal of Arts and was the recipient of 18 honorary doctorates from universities including Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts; Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut; New York University, New York; and Howard University, Washington, D.C. He was a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters and served as a commissioner for the National Council on the Arts.

Jacob Lawrence, The Studio, 1996. Lithograph on paper, 30 x 22 1/8 in. © 2019 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Jacob Lawrence, The Builders (Family), silkscreen on paper, 34” x 25.75”, 1974. © 2018 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The exhibition explores three major themes that occupied the artist’s graphic works. Lawrence started exploring printmaking as an already well-established artist. Printmaking suited his bold formal and narrative style exceptionally well. The relationship between his painting and printmaking is intertwined, with the artist revisiting and remaking earlier paintings as prints. The inherent multiplicity of this medium provided an opportunity for the artist to reach broader audiences.

Jacob Lawrence, "The Card Game," tempera on board, 19" x 23½", 1953. Gift of Dr. Walter O. and Mrs. Linda J. Evans. SCAD Museum of Art Permanent Collection. © 2017 Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle/Artists Rights Society, New York.

Lawrence was primarily concerned with the narration of African-American experiences and histories. His acute observations of community life, work, struggle and emancipation during his lifetime were rendered alongside vividly imagined chronicles of the past. The past and present in his practice are intrinsically linked, providing insight into the social, economic and political realities that continue to impact and shape contemporary society today.

Jacob Lawrence, “The Builders (Family),” silkscreen on paper, 34” x 25.75”, 1974. © 2018 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Jacob Lawrence: Forward Together (Harriet Tubman and the Underground Railroad) (1997), silkscreen, 25″ x 40″

The Life of Toussaint L’Ouverture, No. 22: Settling down at St. Marc, he took possession of two important posts (detail), 1938. Jacob Lawrence (American, 1917–2000). Tempera on paper; 19 x 11 1/2 in. Courtesy Amistad Research Center, Tulane University, New Orleans, Aaron Douglas Collection.

Eventually, Lawrence would create 41 panels about Toussaint L’Ouverture and the struggle for Haitian self-governance. A gifted printmaker, he decided to create a portfolio of 15 screenprints based on the panels.

Echoing Thomas Jefferson’s words that “all men are created equal,” Toussaint L’Ouverture said, “I was born a slave, but nature gave me the soul of a free man.” This sentiment informed his leadership of the Haitian Revolution, and created what was the first free colonial state in which race was not a factor in determining social status.

Jacob Lawrence, Flotilla from Toussaint L’Ouverture, 1996. Screenprint. The Harmon and Harriet Kelley Foundation for the Arts. ˝ 2017 Jacob Lawrence / Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York

Photograph courtesy Davidson Galleries, Seattle.

Jacob Lawrence (1917-2000)

Subway Acrobats

Pr.$968,000

Jacob Lawrence, “New York in Transit I,” 1998, silkscreen, edition of 50 with 5 AP, © 2015 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/8f/dc/8fdc0c21-0aba-40a0-a040-7abf57215012/blogjlawsus1800_003.jpg)

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/71/8a/718a4b1f-7c0e-4179-b472-1f9a456a2a9e/exjlsli003.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpeg)

No comments:

Post a Comment