Romare Bearden: Abstraction, an important traveling exhibition organized by the American Federation of Arts and The Neuberger Museum of Art, Purchase College, SUNY, is comprised of approximately 55 works by the ground-breaking African American artist. Romare Bearden: Abstraction presents the first in-depth examination of Bearden’s engagement with abstraction.

Through paintings, collages, watercolors and photostats ranging from the 1940s to the late 1960s, the exhibition explores and contextualizes Bearden’s important, but relatively unknown, body of abstract work alongside his early figural abstractions and more well-known figurative collages. Central to the exhibition are a group of Bearden’s rarely exhibited stain paintings created between 1952-1963 that reveal a masterfully distinctive experimentation with color and form unlike anything the artist had created before. This important yet underrecognized period in Bearden’s career laid the framework for the celebrated figurative collages that the artist began producing in 1964.

The exhibition was originated by the Neuberger Museum of Art, with the national tour of Romare Bearden: Abstraction to launch in October 2021 with presentations at the Gibbes Museum of Art, Charleston, SC (October 15, 2021 – January 9, 2022); the University of Michigan Museum of Art, Ann Arbor, MI (February 5 – May 15, 2022); and the Frye Art Museum, Seattle, WA (June 25 – September 18, 2022).

“Romare Bearden is one of the 20th century's great American artists," said Pauline Willis, Director and CEO of the American Federation of Arts. "While Bearden's significance is recognized by the public and art establishment alike, the many layers of innovation within his body of work are relatively unknown. It is with enormous pleasure that the American Federation of Arts presents the important traveling exhibition Romare Bearden: Abstraction that is valuable to scholars and will also bring joy and enrichment to audiences across the United States, reaching from the American South to the Midwest and the Pacific Northwest."

According the exhibition curator, Dr. Tracy Fitzpatrick, “Prior to this exhibition, very little substantive scholarly attention had been paid to the body of work that directly precedes the works for which Bearden is best known. Romare Bearden: Abstraction corrects that omission by providing the first substantive and scholarly examination of this extraordinary non-representational, large-scale stain paintings and mixed media collages important body of work. The project contributes to the development of alternate storylines around the dominant narrative of post-war abstraction while at the same time revealing, for the first time, the roots of the body of work for which Bearden is best known."

Romare Bearden and the Road to Abstraction

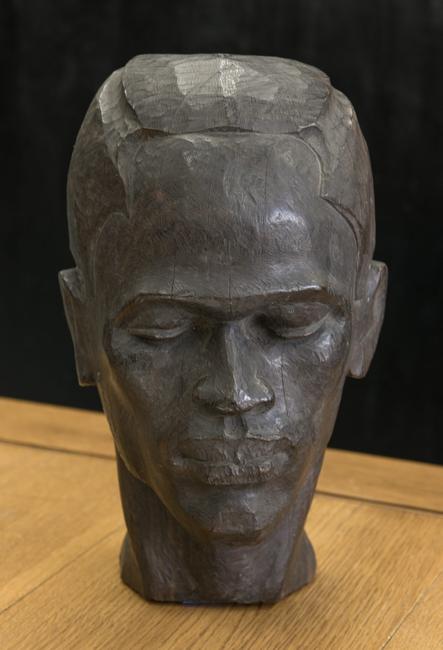

Romare Bearden was born in Charlotte, North Carolina in 1911. In 1914 his parents relocated the family to Harlem as part of the “Great Migration,” during which many southern-born African Americans fled north to escape the Jim Crow South. Bearden began his training in the 1930s, studying art alternately at New York University, Boston University, and at the Art Students League under the tutelage of George Grosz. This diversity of influences contributed to a rich artistic education; and by 1940, Bearden secured his first solo show in New York. Assembled chronologically and according to medium, this exhibition emphasizes the importance of Bearden’s abstract paintings and collages in the course of his formal development, including examples of the abstracted figural compositions from the mid-1940s and the mature collages for which he is widely regarded today.

Though initially rooted in the figurative tradition, Bearden progressively moved towards abstraction in the 1940s. A breakthrough came in 1945 when Bearden’s work was included in a group exhibition at the Maeght Gallery in Paris. Shown alongside works by William Baziotes, Adolph Gottlieb, and Robert Motherwell, Bearden was rightly associated with the leading contemporary artists of the American vanguard. Following the positive reception of an exhibition in Washington, DC, Bearden was offered representation by the influential New York gallerist and proponent of abstraction, Samuel M. Kootz. Works from this period illustrate both the artist’s affinity for abstracted forms as well as his remarkable facility with watercolor and ink.

Following the closure of the Kootz gallery in 1948 and a brief sojourn in Paris, Bearden began fully engaging with non-representational subjects in the 1950s. The abstract works from this period are striking for their exceptional quality, variety and scale. Easel size watercolors and oil paintings such as Blue Ridge (ca. 1952) and Mountains of the Moon (1955) show Bearden’s singular interpretations of landscape through abstraction.

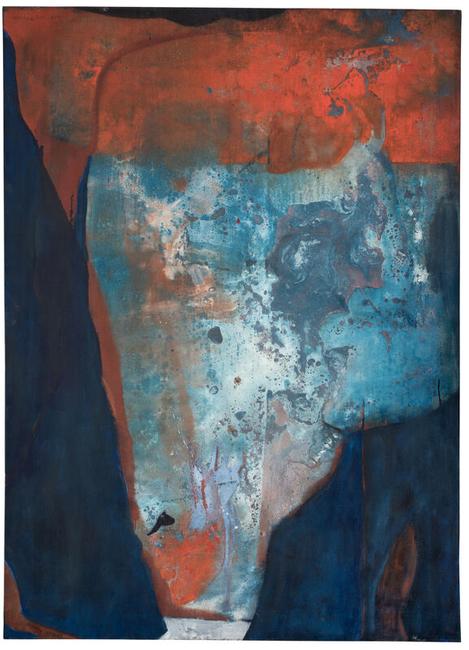

Though initially reluctant to work in oil, Bearden’s skill in the medium reached its apex in the late 1950s and early 1960s, when he was introduced to Chinese ink wash painting by a local bookseller. Inspired by this technique, Bearden began thinning oil paint with turpentine to achieve a more fluid facture, closer to the watercolor that he was most comfortable with. Applying thinned pigment to unsized canvas—what is now commonly referred to as stain painting—was a method employed by several other artists during this period, including Helen Frankenthaler, Morris Louis, and Kenneth Noland. Bearden’s work ranks among the best examples of this innovative application; realized in both luminous tones and somber hues, these paintings are exemplary of the artist’s remarkable sensitivity to color. Works such as Green Torches Welcome New Ghosts (1961) show Bearden enthusiastically brushing, pouring, and spraying diluted oil, while the curving lines of Eastern Gate (1961) reveal the inspiration of Chinese calligraphy.

Bearden continually reimagined his approach to artmaking. By mixing thinned oil pigment together with casein and then painting it on sized canvas or paper, he relied on the immiscibility of oil and water to create a marbled effect. With Blue (1962) and Strange Land (1959) epitomize the marbleized patterns; these compositions are suggestive of natural substances, as though seeing the speckled and veined qualities of rocks and plants in magnified detail. Bearden combined oil and collage in another group of works he was producing at this time, which he began by cutting up his paintings and then collaging them onto painted boards. River Mist (1962) is a work of washed and splattered blues reminiscent of moving water, with areas of painted oranges and white stained canvas. The painted elements are cut, then fitted together and finally adhered to a brown painted board. Such works are clear precursors to the figurative collages produced after 1964.

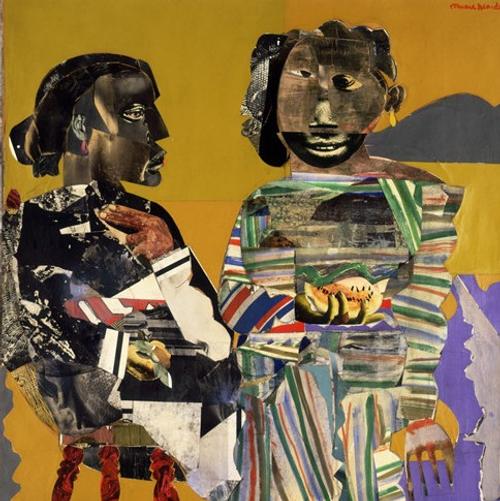

Bearden premiered a new body of work in October 1964. Collectively titled “Projections”, these works represent yet another innovative development in the artist’s body of work. Perpetually intrigued by collage, Bearden began utilizing cut paper to form representational images rather than abstract arrangements. First created at small scale and then enlarged via photostatic reproduction, this process would eventually culminate in the large-scale figurative collages that Bearden created for the rest of his career.

Although his abstract work was well-received contemporaneously in galleries and by the press, Bearden chose to adopt figuration as his primary artistic mode after 1964. While several of the abstract compositions are included in public and private collections, many have remained in storage since they were first exhibited, while others have never been shown outside of this exhibition. Romare Bearden: Abstraction serves as a rare opportunity for public view of these important abstract works and an invitation to reassess the career of one of the foremost American artists of the postwar era.

|

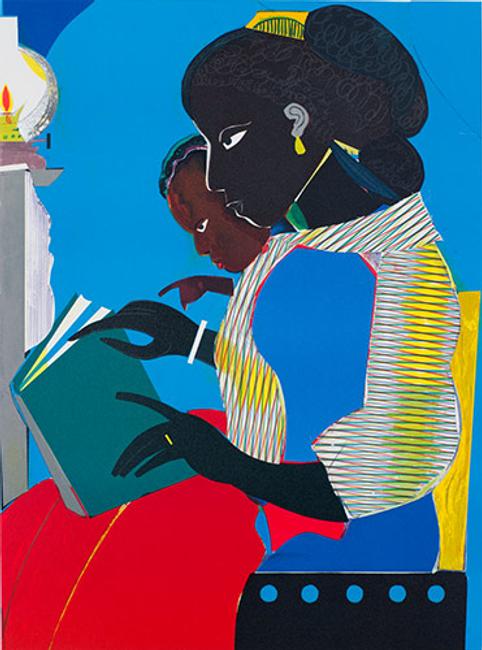

Reynolda House Museum of American Art founding director, Barbara Babcock Millhouse, has generously promised a gift of two collages by the celebrated African American artist Romare Bearden. In Alto Composite, 1974, the artist conveyed his deep love for jazz and blues. Using highly saturated colored paper, Bearden created a stylized, Cubist-inspired saxophone player. Unlike other collages in his 1974 Of the Blues series, which are populated with multiple figures playing music and dancing, Alto Composite includes just one musician, monumentalized against a multi-hued background. The high contrast of colors creates a sense of energy and dynamism that reflects the music that inspired the artist.

Bearden’s Moonlight Express, 1978, demonstrates the way the artist, over and over again in his work, turned to a complex set of symbols. They included masks, large hands, trains, suns and moons, “conjur” or medicine women, music and musicians, and animals of all kinds. Moonlight Express features several of these motifs. At left, the artist’s iconic train carried African Americans from their native South to new lives in the North, and sometimes back south again. In a dark forest, white birds spread their wings, which glow in the light of a full moon. And, in the lower left, Bearden has included the figure of a woman. Her nudity and her presence in the forest mark her clearly as a conjur woman, a kind of voodoo priestess who lends a note of mystery to the scene.

Both collages by Bearden will be on view in the spring of 2022 in an exhibition exploring collage as a medium.

Dox Thrash, Saturday Night, c. 1944-45, etching. Courtesy of Dolan/Maxwell.

Dox Thrash, Cabin with a Star in the Window, c. 1944–45, carborundum mezzotint, proof reworked in ink. Private collection, image courtesy of Dolan/Maxwell.

Image: Penn State

Dox Thrash, Black Life, and the Carborundum Mezzotint brings together numerous examples of the experimental process by Thrash and other colleagues working in the Fine Print Workshop. Also on view are works by Thrash in other print mediums, as well as watercolors and drawings, all of which powerfully document the artist’s intimate, invested engagement with African American culture in the middle decades of the twentieth century.Dox Thrash, "Life," c. 1938–39, carborundum mezzotint, 10 7/8 x 8 13/16 inches.Image: Dox Thrash / Courtesy of Dolan/Maxwell

Dox Thrash, "Defense Worker", c. Carborundum mezzotint over etched guidelines.

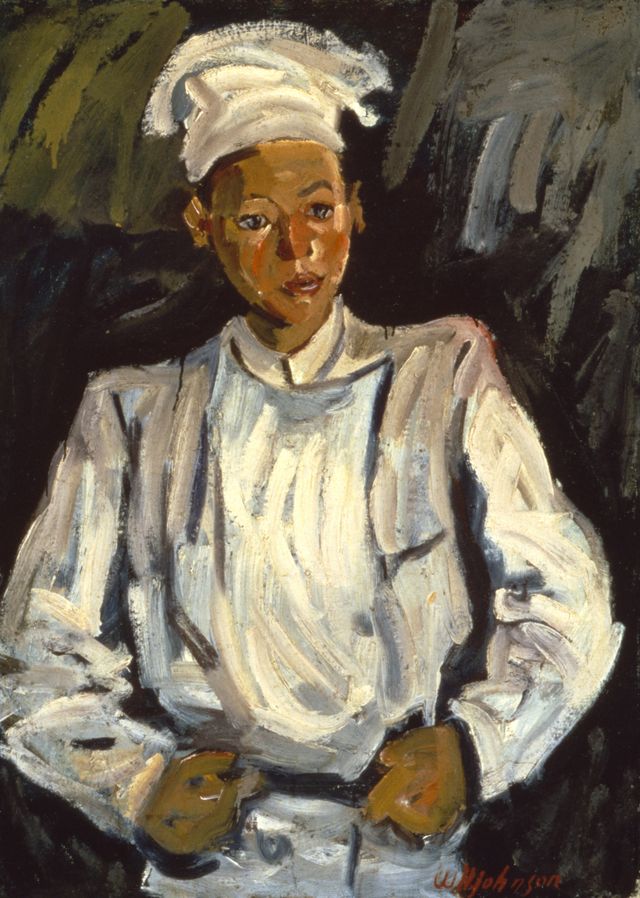

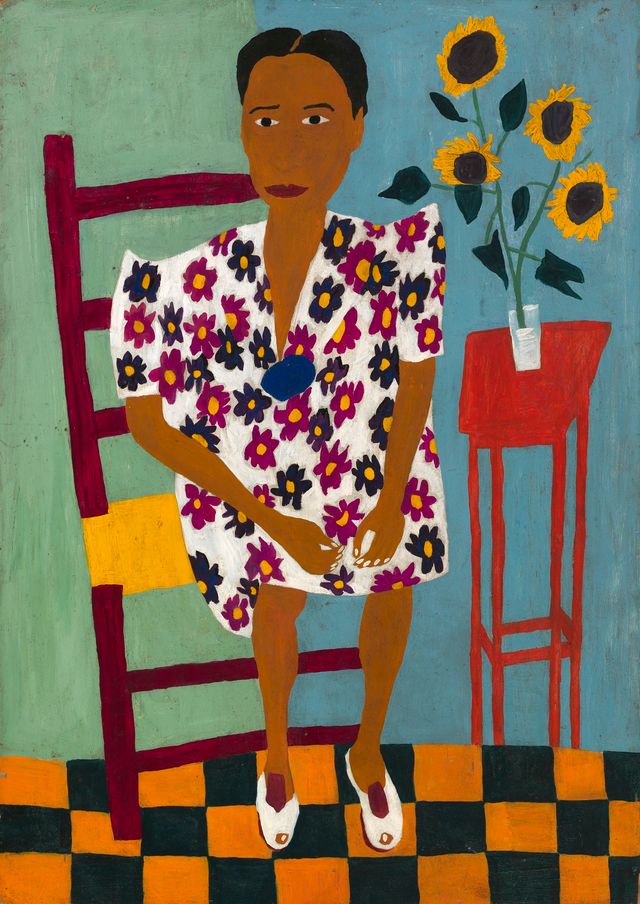

Johnson spent decades traveling the world, searching for the authentic spirit of ordinary people from different cultures. In the late 1930s, he found what he was looking for in his own African American community. The strong colors and silhouettes in this painting evoke the African art that black artists and writers had embraced during the Harlem Renaissance. But this affectionate couple also had the fashionable flash of zooit-suiters in the big band era. Above the table, the two figures coolly take in the café scene; below, a tangle of legs and limbs hints at the erotic energy of a night on the town.

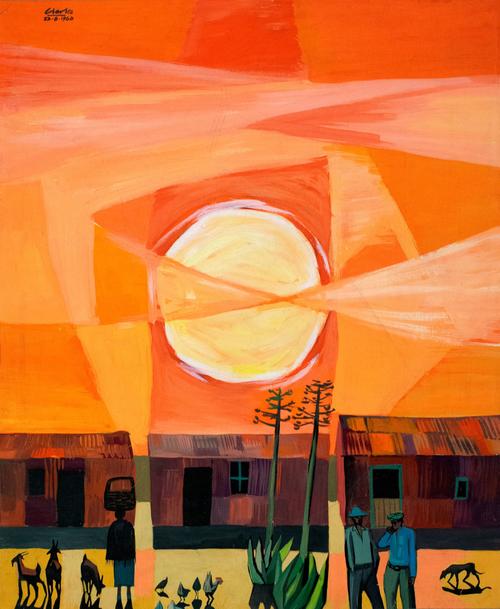

Sowing presents a simple narrative of farm life suggestive of Johnson’s upbringing in South Carolina, but the brilliant palette disguises elements of tension. The plow the man grips is stained with red streaks of iron-suffused earth. The woman’s hand is tightly clenched as she holds the seed above the soil before releasing it. A ghost moon in the sky hints at things both visible and unseen.