Also see:

https://www.hydecollection.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Thrash-online-exhibition2.pdf

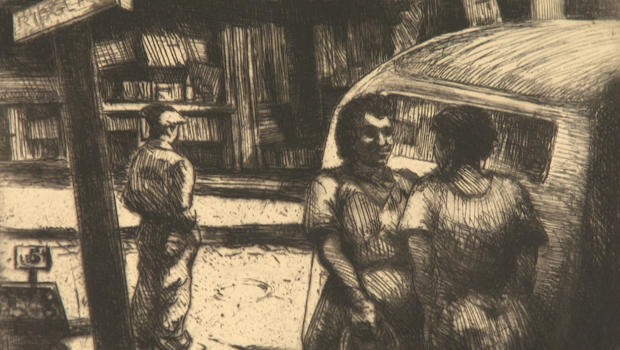

Dox Thrash, Saturday Night, c. 1944-45, etching. Courtesy of Dolan/Maxwell.

Dox Thrash, Cabin with a Star in the Window, c. 1944–45, carborundum mezzotint, proof reworked in ink. Private collection, image courtesy of Dolan/Maxwell.

Image: Penn State

In 1937, Thrash signed on for employment with the Federal Art Project’s Fine Print Workshop. There, while working with fellow artists Hugh Mesibov and Michael Gallagher, he began to experiment with a new approach to intaglio printmaking, which today is known as the carborundum mezzotint process. With its broad tonal range, the new process was ideally suited to the sensitive portrayals of Black life for which Thrash would become known.

Dox Thrash, Black Life, and the Carborundum Mezzotint brings together numerous examples of the experimental process by Thrash and other colleagues working in the Fine Print Workshop. Also on view are works by Thrash in other print mediums, as well as watercolors and drawings, all of which powerfully document the artist’s intimate, invested engagement with African American culture in the middle decades of the twentieth century.Dox Thrash, "Life," c. 1938–39, carborundum mezzotint, 10 7/8 x 8 13/16 inches.

Dox Thrash, "Defense Worker", c. Carborundum mezzotint over etched guidelines.

In much of his work, Thrash portrays black

families transitioning from the South to the North during the Great

Migration, making a hopeful, daring leap to attempt to be equal members of the

society that has historically oppressed them. Their hopeful gazes convey the

optimism of the scores of

African Americans who left the countryside to pursue better job opportunities, health care, and education

in urban centers.

·

Start with one work,

"Glory Be!" This small, deeply inky intaglio print by Dox Thrash,

made in the first years of World War II, shows a

half dozen people looking and pointing upward. This is a religious moment,

silhouettes before a wild ivory-white background that almost looks like fire,

and we see the striving emotive possibilities of such a fervent meeting with

just the large effect of shapes and light.

Nearby is a drawing

with more detail, a mirror image version that was the study for the print. The

print has more power because it shows less, and it does so with material

richness. This was made with a new process, the carborundum mezzotint, invented

in part by the artist as an innovation based on traditional mezzotint.

The new show at the

Hyde, "Dox Thrash, Black Life, and the Carborundum Mezzotint,"

circles around this technique. These prints, the real high points of

Thrash's career, might be outnumbered by watercolors, drawings, and etchings,

but the show gives a fuller measure of this African-American's contribution to

20th-century American art.

The contribution

lies foremost not in the carborundum process, as important as that is, but in

the content of the artist's work. There are simple evocations of everyday life

like "Churning Butter," presented in two different mezzotint

versions, and there are portraits, several of them bold and brooding, using a

variety of techniques. The many portraits alone recall for me how often I've

heard African-American students remark how bracing and positive it is for them

to see images — photographs or paintings — that represent them. It matters more

than you might imagine.

"Saturday

Night" is a carborundum relief etching from 1944-45, a complex version of

the usual method that adds greater linear clarity to the broader textural

effects of the mezzotint. In it we see a woman preparing for a night out, and

its plain but elegant tenderness recalls Degas and Cassatt. "The

Champ" is an aquatint depiction of the boxer Joe Louis, with surfaces

writhing in dark black and warm brown details that plunge into sadness and intensity.

The portraits,

figure studies, and scenes with houses and buildings build a picture of a world

that was underrepresented, and is vigorously given moody depth with these new

techniques. It was in December 1937 that Thrash first stumbled on the beginnings

of his novel mode of intaglio. He used a rough carborundum powder to rub a

copper plate, and the surface with all its shards of metal that he said

"stick up like hills" allowed for selective burnishing and then

inking and printing.

The

complexity of tones possible, depending on the amount of burnishing, made for a

20th-century aquatint that gave dark, deep prints favoring tonal effects over

specific details. Look into the darkness of "Cabin Days," where both

the sunset sky and the foreground fence and

driveway embrace the key detail in the center, a service star in the window of

the simple cabin.

Thrash

was born in Georgia and joined the great northward migration of

African-Americans in midcentury, going first to Chicago and serving in World

War I before eventually making Philadelphia his home. It was there, with the

help of the WPA, that he joined the Fine Print Workshop in 1937, and his career

solidified as he worked on his new printing process.

It's

natural to compare Thrash to more famous black artists like Jacob Lawrence and

Romare Bearden, since they or their families were all part of the Great

Migration, but Thrash was a generation earlier, a breakthrough artist more

closely aligned to the Harlem Renaissance and what was called the New Negro movement,

which defined black Americans objectively, against stereotypes. Thrash's

portraits give dignity and honesty to his subjects, and his depictions of

buildings or occupations do not avoid the poverty and difficult lives people

faced.

If

Thrash is less convincing in his watercolors, the subjects are still

significant: a baptism at the shore, row houses and a rail yard, and a series

of portraits. But the prints — the etchings, lithographs, aquatints, and most

of all his specialized mezzotints — are bold and beautiful, laying bare a part

of the world receding fast into history.

No comments:

Post a Comment