William H. Johnson (1901–1970) painted his last body of work, the “Fighters for Freedom” series, in the mid-1940s as a tribute to African American activists, scientists, teachers and performers as well as international leaders working to bring peace to the world. The landmark exhibition “Fighters for Freedom: William H. Johnson Picturing Justice,” brings together—for the first time since 1946—34 paintings featured in the series, including 32 drawn from the museum’s collection of more than 1,000 works by Johnson.

Two paintings, “Three Great Freedom Fighters” and “Against the Odds,” are on loan from the Hampton University Museum of Art exclusively for the presentation at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. The exhibition illuminates the extraordinary life and contributions of Johnson, an artist associated with the Harlem Renaissance but whose practice spanned several continents, as well as the contributions of historical figures he depicted.

“Fighters for Freedom: William H. Johnson Picturing Justice” is on view from March 8 through Sept. 8 at the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s main building in Washington, D.C. It is organized by Virginia Mecklenburg, senior curator at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, and Laura Augustin Fox, curatorial collections coordinator.

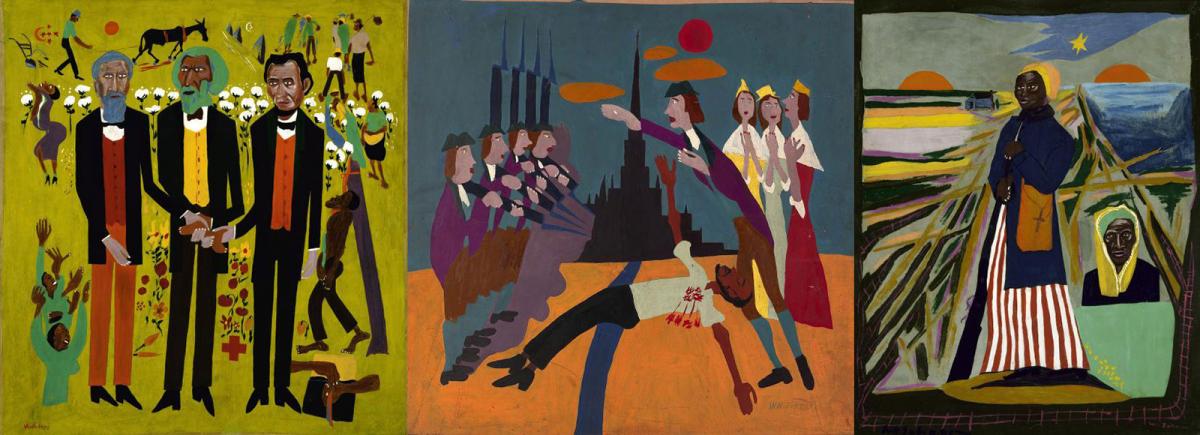

Examples of three paintings from William H. Johnson's Fighters for Freedom series (left to right): Three Great Abolitionists: A. Lincoln, F. Douglass, J. Brown (ca. 1945), Crispus Attucks (ca. 1945), and Harriet Tubman (ca. 1945).“

By telling the stories of those who fought for social and racial justice, both historically and in his own time, the remarkable artist William H. Johnson should be more widely known and this exhibition aims to do that by reaffirming the central importance of African Americans to the American narrative,” said Stephanie Stebich, the Margaret and Terry Stent Director. “It is an awesome and humbling responsibility to build on more than 50 years of the Smithsonian American Art Museum of preserving, displaying and interpreting a lifetime of work by this great American artist whose bold graphic images are not soon forgotten.”

Some of Johnson’s “Fighters”—Marian Anderson, George Washington Carver, Mohandas Gandhi and Harriet Tubman—are familiar figures; others—Nannie Helen Burroughs and William Grant Still, among them—are less well-known individuals whose achievements have been eclipsed over time. Johnson celebrates their accomplishments even as he acknowledges the realities of racism, oppression and sometimes violence they faced and overcame. Johnson clues viewers to significant episodes in the “Fighters” lives by punctuating each portrait with tiny buildings, flags and vignettes that give insight into their stories. Using a colorful palette to create evocative scenes and craft important narratives, he suggests that the pursuit of freedom is an ongoing, interconnected struggle, with moments of both triumph and tragedy. These paintings invite the viewer to reflect on the struggles for justice today.

“Through Johnson’s ‘Fighters for Freedom’ paintings, we learn about people who changed lives, promoted equality, valued legacy and demonstrated unflagging determination in the face of almost insurmountable challenges,” Mecklenburg said. “He tells us that the continued fight for equity, dignity and equality for all is central to the American story.”

The museum has created extensive educational materials and in-gallery interpretation strategies to deepen visitors’ understanding of Johnson and the featured historical figures. A visual timeline puts Johnson’s life events in context with key moments in African American history and the lives of his “Fighters.”

The museum has produced short videos to accompany five paintings on view, each featuring commentary from curators from across the Smithsonian discussing collection objects, including Nat Turner’s Bible and Marian Anderson’s fur coat, that give insight into the people depicted in each work. Four interactive in-gallery kiosks provide information about Johnson’s visual references and historical source material that “decode” selected compositions and uncover the meaning behind the imagery. A separate media space invites visitors to experience select “Fighters” in action through archival video, audio and images. The museum’s efforts to conserve Johnson’s artworks are documented in a short video and wall panels, highlighting the recent preservation work of the “Fighters for Freedom” paintings. Additional elements include tactile reproductions and visual descriptions of key works; an all ages reading room that offers visitors a chance to gather, learn and reflect; and a mural featuring responses from students across the country about people they consider fighters for freedom today.

About William H. Johnson

Johnson was born in Florence, South Carolina, in 1901, but left the Jim Crow South as a teenager to go to New York City. In 1921, he passed the entrance exam at the National Academy of Design. By the time he finished five years later, he had won most of the prizes the academy offered. Johnson left for Europe, where he painted landscapes that marked him as an up-and-coming modernist. After three years in France, Johnson returned to the United States in 1929, meeting Harlem Renaissance luminaries Alain Locke and Langston Hughes during that time. He left again for Europe after less than a year. He married Danish weaver Holcha Krake in 1930, and they spent most of the decade in Scandinavia, where Johnson's interest in European modernism had a noticeable impact on his work.

In late 1938, with World War II imminent, the couple returned to New York, where he was soon recognized as a central figure in the Harlem Renaissance. Johnson abandoned the dazzling landscapes he painted in Scandinavia to focus instead on the lives of African Americans. He painted Southern sharecroppers, city hipsters, Black soldiers training for war, religious scenes and his last series, “the Fighters for Freedom.” It was a trying time in Johnson’s personal life. His wife developed breast cancer, and after she died in 1944, Johnson’s mental health deteriorated. In 1947, he was confined to Central Islip State Hospital in New York, where he remained until his death in 1970.

In 1967, the William E. Harmon Foundation, the patron of African American artists that cared for Johnson’s work after his hospitalization, entrusted his life’s work—paintings, watercolors, prints and drawings—to the Smithsonian American Art Museum. The museum, in turn, offered almost 150 paintings and prints to other institutions. As a result, historically Black universities, including Fisk, Hampton, Howard, Morgan State and others, have rich collections of Johnson’s work. The Smithsonian American Art Museum holds the largest and most complete collection of work by Johnson. It has done much in the past 50 years to preserve Johnson’s art and establish his reputation by organizing exhibitions and installations of his work and an ongoing program of conservation for these fragile paintings. Most recently, the museum has loaned six works by Johnson to the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s groundbreaking exhibition “The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism” (2024).

Book

A beautifully illustrated catalog accompanies the exhibition, co-published by the Smithsonian American Art Museum in association with Scala Arts Publishers Inc. It is written by Mecklenburg, with an introduction by Smithsonian Secretary Lonnie G. Bunch III, a foreword by Stebich and contributions by Tiffany D. Farrell and Emily H. Rohan. It is available for purchase ($34.95, softcover) in the museum store and online.

No comments:

Post a Comment