-----at Swann

The December 10, 2020, sale of African American Art was met with enthusiasm from collectors. The sale saw nine auction records set, as well as an auction debut from contemporary artist Tyrone Geter. The auction total reached $2.8 million bringing the house’s African American Art sale totals for the year to $9.2 million.

Charles Alston

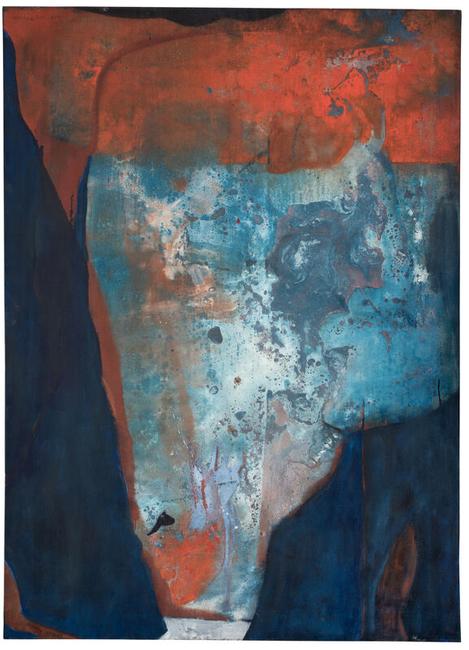

Leading the December sale was Charles Alston’s Black and White #8, oil on canvas, 1961. The largest of the artist’s works yet to come to auction, the stunning abstraction came from an important series of eight works painted between 1959 and 1961. Black and White #8, earned a record for the artist at $197,000.

Abstract Works

Additional abstract works included Sir Frank Bowling’s Repose for SO, acrylic on canvas, 1976, an example of Bowling’s trailblazing mid-1970s series of “poured paintings,” which brought $93,750. Kenneth Victor Youngand Thomas Sills returned to the Swann auction block after stellar outings in the January white-glove sale of the Johnson Publishing Company’s art collection. Young was present with a circa-2000 acrylic-on-canvas abstraction in fuchsia and blue, which sold for $81,250, and Sills was featured with New Born, oil on canvas, 1958, at $50,000. A 1972 acrylic-on-paper in dark blue-black and deep pink by Alma Thomas earned $62,500; and a 1978 color pastel, dry pigment and pencil work from Ed Clark’s Louisiana Series realized $60,000.

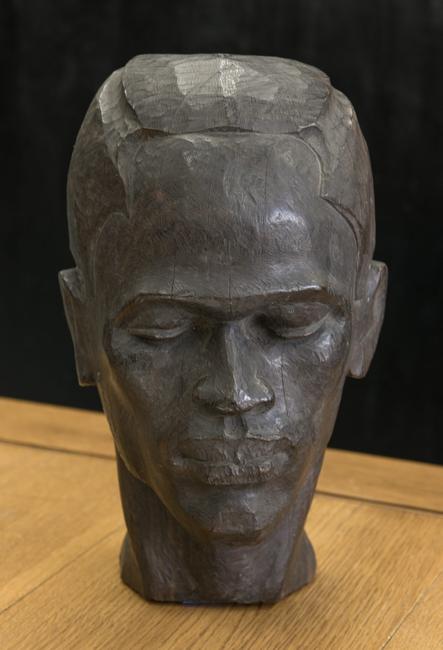

Augusta Savage & Sculpture

Augusta Savage earned a new auction record with the sale of her iconic 1929 sculpture Gamin. The work was acquired directly from the artist before it made its way across the auction block, selling for $112,500. Also representing sculptural works was Simone Leigh with Head, a 2004 glazed and painted fired stoneware work that brought $93,750.

Related Reading: Fine Sculpture by African-American Artists

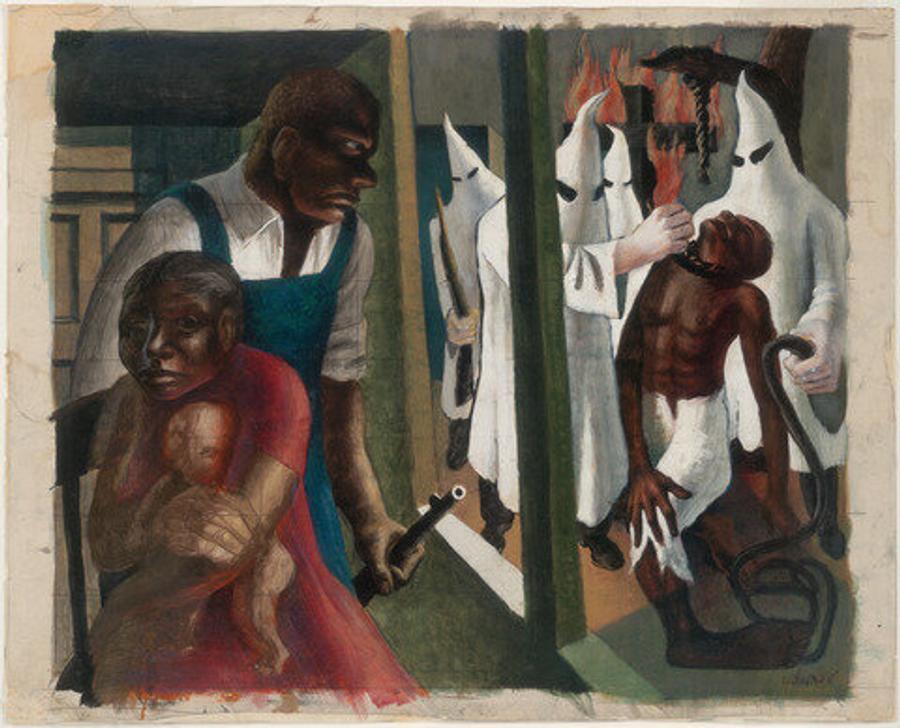

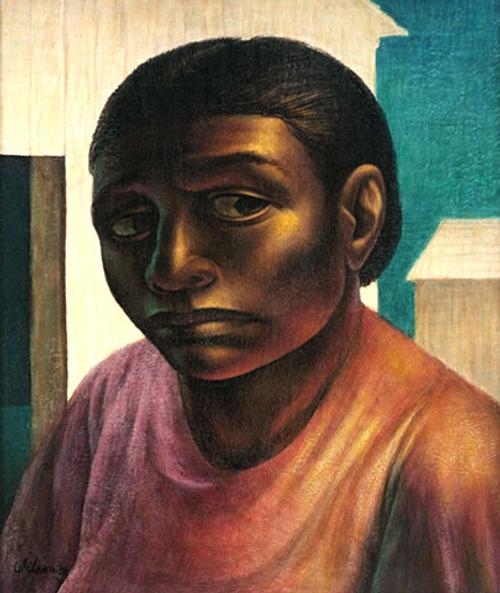

Figurative Works

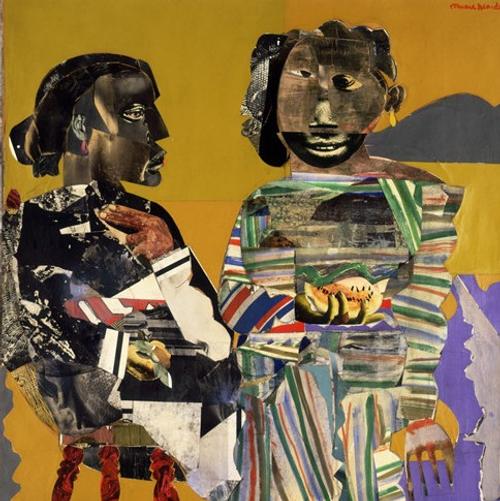

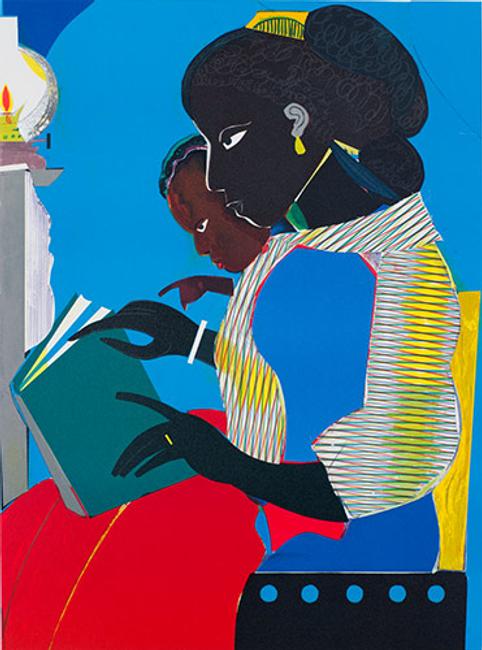

Figurative works included Wadsworth Jarrell’s Subway, acrylic on canvas, 1970, which brought a record for the artist at $125,000. Another record was earned with John N. Robinson’s 1952 oil-on-canvas portrait of his wife Gladys at $81,250. Romare Bearden was present with two collage works: Woman and Child, 1968, which sold for $173,000, and The Last of the Blue Devils, 1979, which sold for $100,000. Also of note was Emma Amos’s Water Baby, a 1987 acrylic and fabric collage with Kente cloth borders of from Amos’s body of work depicting women bathers, crossing the block at $100,000, the second-highest price at auction behind Let Me Off Uptown, which sold at Swann in 2019 for $125,000.

Related Reading: A Brief History of AfriCOBRA

“Despite the turbulent year, I am thrilled to see the continued growth of our sales, and the rising recognition of the great artists featured: from Harlem Renaissance masters Augusta Savage and Charles Alston to prized postwar painters Wadsworth Jarrell and John N. Robinson. We had a tremendous level of interest in the sale overall with an increasing diverse audience of individual collectors and institutions from around the world.”

Nigel Freeman, Director, African American Art

Sale total: $2,761,105

Estimates for sale as a whole: $2,220,000–$2,229,500

We offered 211 lots; 174 sold (82% sell-through rate by lot)

All prices include Buyer’s Premium.

Quote from Director of African American Art Nigel Freeman: “Despite the turbulent year, I am thrilled to see the continued growth of our sales, and the rising recognition of the great artists featured: from Harlem Renaissance masters Augusta Savage and Charles Alston to prized postwar painters Wadsworth Jarrell and John Robinson. We had a tremendous level of interest in the sale overall with an increasing diverse audience of individual collectors and institutions from around the world.”

Top lots Prices with buyer’s premium

41† Charles Alston, Black and White #8, oil on linen canvas, 1961. $197,000

83 Romare Bearden, Woman and Child, collage of various colored and printed papers and pencil, 1968. $173,000

73† Wadsworth Jarrell, Subway, acrylic on canvas, 1970. $125,000

11† Augusta Savage, Gamin, plaster painted gold, circa 1929. $112,500

91 Romare Bearden, The Last of the Blue Devils, collage on board, 1979. $100,000

151* Emma Amos, Water Baby, acrylic and fabric on canvas with Kente cloth border, 1987. $100,000

192 Simone Leigh, Head, glazed and painted fire stoneware, 2004. $93,750

118 Sir Frank Bowling, Repose for SO, acrylic on canvas, 1976. $93,750

188 Kenneth Victor Young, Untitled, acrylic on cotton canvas, circa 2000. $81,250

28† John N. Robinson, Reclining Woman (Gladys), oil on canvas, 1952. $81,250

82 Alma Thomas, Untitled (Composition in Dark Blue Black and Deep Pink), acrylic on paper, 1972. $62,500

119 Ed Clark, Untitled (Louisiana Series), color pastel, dry pigment and pencil on paper, 1978. $60,000

15 Norman Lewis, Untitled (Head of a Mule, French Sudan), color pastel on fine sandpaper, 1935. $60,000

39 Thomas Sills, New Born, oil on cotton canvas, 1958. $50,000

60 Bob Thompson, Tancred and Erminia, oil on paper mounted on board, circa 1965. $50,000

154 Hughie Lee-Smith, Man with White Flag, oil on linen canvas, 1987. $40,000

112 Charles White, Dr. W.E.B. DuBois, charcoal and crayon on paper, 1974. $37,500

58 Benny Andrews, Bather on the Horizon, oil on canvas, 1964. $35,000

122 Dinga McCannon, Black Family, oil, metallic paint and fabric collage on canvas, 1980. $30,000

52 Charles White, Little Boy Walking (Child Walking), pen and ink wash on paper, 1966. $27,500

Key: † = Auction Record for the Artist; * = Second Highest Price at Auction

Additional Artist Records: Lot 35 – Edward Loper, Sr., $13,750; Lot 37 – Gloucester Caliman Coxe, $10,625; Lot 144 – Frank Hayden, $10,000; Lot 3 – James V. Herring, $7,500; and Lot 126 – Lev Mills, $5,750

Auction Debuts: Lot 209 – Tyrone Geter, $9,375

Additional highlights can be found here.

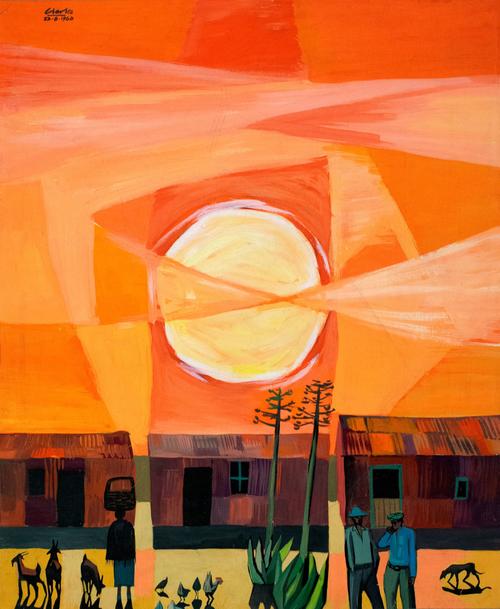

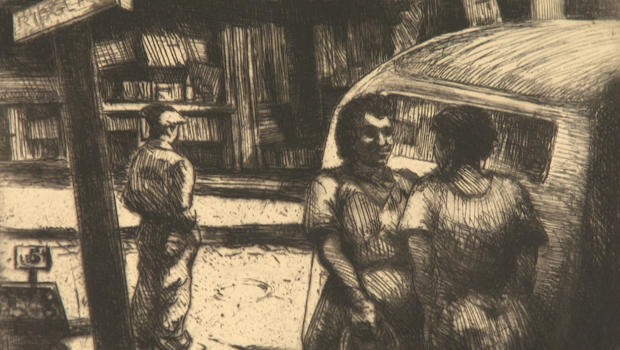

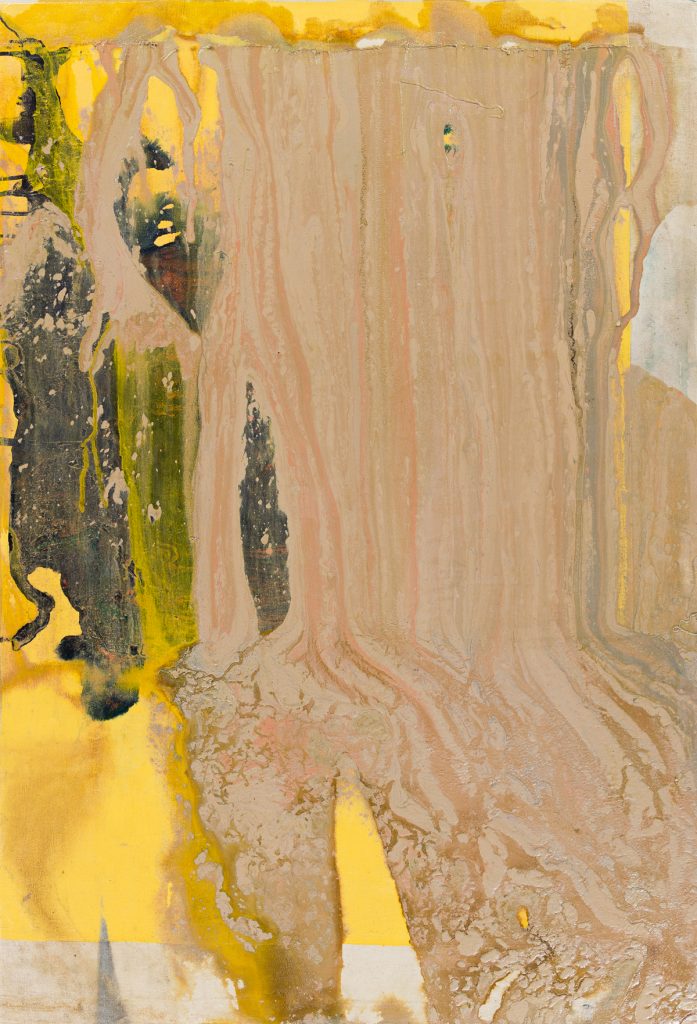

Captions:

Lot 41: Charles Alston, Black and White #8, oil on linen canvas, 1961. Sold for $197,000, a record for the artist.

Lot 11: Augusta Savage, Gamin, plaster painted gold, circa 1929. Sold for $112,500, a record for the artist.