Faith Ringgold was an artist from Harlem, New York, who created provocative artworks that responded to the civil rights and feminist movements. In honor of what would have been Ringgold’s 95th birthday, today we’re sharing 5 facts you might not know about her life and practice!

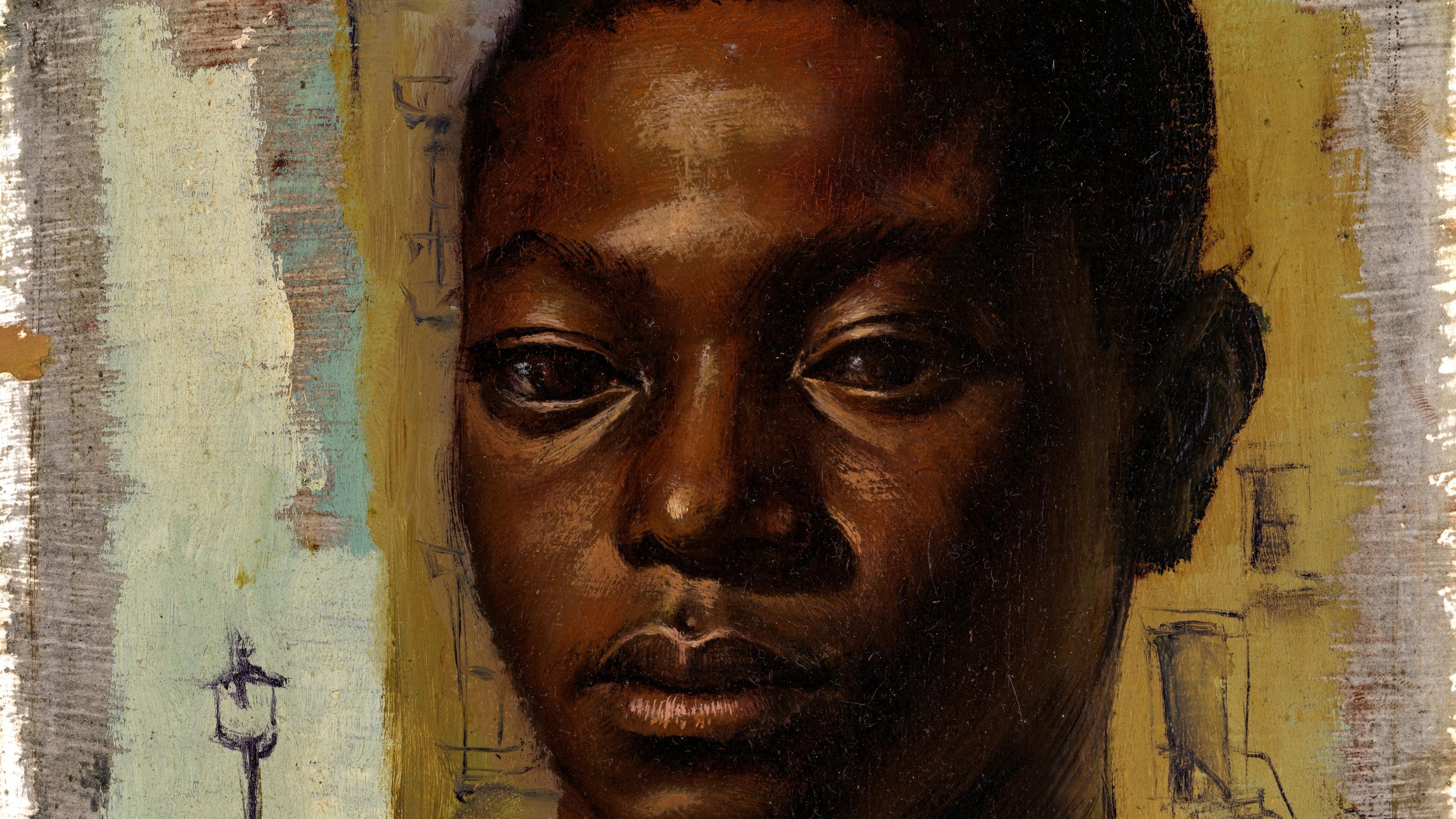

“While the powerful impact of John Wilson’s art and the enduring relevance of the themes he explored are undeniable, he has not yet received the recognition his work so deeply deserves,” said Max Hollein, Marina Kellen French Director and Chief Executive Officer of The Met. “This landmark exhibition honors Wilson’s extraordinary artistic achievements—illuminating the incredible range of work he produced over five decades—and affirms his place in art history as one of the foremost artists devoted to social justice and portraying the experiences of Black Americans.”

Jennifer Farrell, exhibition co-curator and Jordan Schnitzer Curator in the Department of Drawings and Prints at The Met, said, “Wilson’s art is imbued with compassion and empathy while conveying his anger and distress at the wrenching effects of disenfranchisement, racism, and economic inequality. Challenging deep-seated prejudices and omissions within our national history, Wilson centered the experiences of Black Americans to create images that convey strength, resilience, and humanity. Deeply personal yet widely resonant, his work continues to offer a powerful lens through which to consider today’s urgent dialogues about race, equality, and representation.”

Leslie King Hammond, exhibition co-curator and art historian, professor emerita, and founding director of the Center for Race and Culture at Maryland Institute College of Art, said, “John Wilson was an artist of profound resilience and passion for the innate essence of dignity, beauty, and humanity of Black Americans, which he witnessed in families, community, and all humankind. He was intentional and relentless throughout his life to create imagery that demanded respect for the Black body in an America struggling with its contested legacy of slavery.”

Working in a figurative style, Wilson sought to portray what he called “a universal humanity.” While still a teenager, he was struck by the absence of positive representations of Black Americans and their experiences in both museums and popular culture. To counter such prejudices and omissions, Wilson put the experiences of Black Americans at the center of his work and created images that portrayed dignity and strength.

The exhibition begins with work Wilson made while in art school in Boston, where his subjects included the horrors of Nazi Germany and American racial violence, as well as portraits of his family and neighborhood. It continues through his time in Paris, Mexico City, and New York, capturing the humanity and scope of Wilson’s art. The exhibition concludes with Wilson’s return to Boston and his focus on portraiture. Included are maquettes and works on paper for two of Wilson’s most celebrated works—his sculpture of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. at the United States Capitol and the monumental sculpture Eternal Presence.

Credits and Related Information

Witnessing Humanity: The Art of John Wilson is co-curated by Jennifer Farrell, Jordan Schnitzer Curator, Department of Drawings and Prints at The Met; Leslie King Hammond, art historian, professor emerita, and founding director of the Center for Race and Culture at Maryland Institute College of Art; Patrick Murphy, the MFA’s Lia and William Poorvu Curator of Prints and Drawings; and Edward Saywell, the MFA’s Chair of Prints and Drawings.

The exhibition is accompanied by a richly illustrated catalogue, jointly authored and edited by the MFA and The Met, and produced by MFA Publications. Reproductions of artworks and photographs accompany critical essays and personal reflections, including analyses by art historians, interviews with Wilson’s peers, remembrances from fellow Black creatives, and a full chronology by the late artist’s gallerist.